Scale Matters

In 2012 I got involved in an ongoing discussion/argument/thread about the difference between strategy and tactics. I followed the discussion for about four weeks before I got tired of the effort needed to strain out the signal of truth from the ocean of noise.

I pondered the question for some time. I could see where, at times, what was a strategy to one company was nothing more than a tactic for another. Scale matters. Consider WalMart’s private fleet. When Sam Walton first started the company, the regulated trucking industry controlled the rate structures. It was expensive to run for-hire carriers to the small towns where Walton’s empire started. If you wanted to move full truckloads of freight to out-of-the-way places cheaply, you had to own the trucks and the drivers. Private fleet was a strategy.

Then WalMart became huge. While it operates one of the largest private fleets in the country (the trash hauler, Republic Industries, is the largest), the fleet is just a part of the massive logistics network used to move freight. Still serving stores and doing backhaul, the fleet is now a tactical method – just one option for moving the freight. The strategy is to use the most cost effective method for that freight to move on time – always. Scale changed the strategy into a tactic.

I started to work to define the difference. My business partner, Mike Starling, and I carried on long discussions on the phone, and in person with cold adult beverages, on how to define the difference. We each had different ideas, but came to consensus about the dividing line in transportation management. We agreed that there are clear strategies and clear tactics in transportation management. We also agreed about a gray area where the difference between tactic and strategy got foggy.

As I kept on working on defining the difference in other areas, I kept thinking that something was missing. I looked at actual events that happened in the past and that were currently happening, looking for examples of what was missing. One then-current event caught my eye, and helped illustrate one of the missing elements, doctrine.

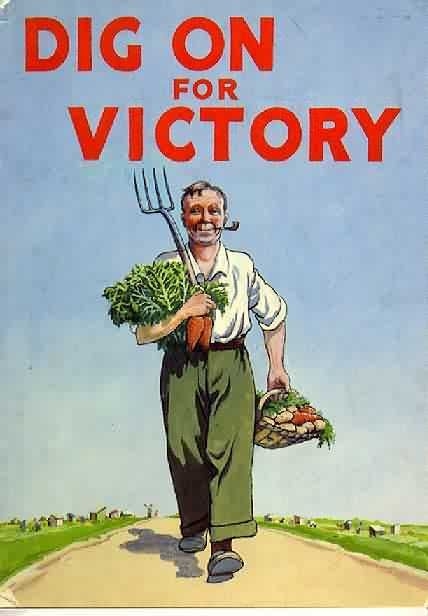

The public failure and ouster of Ron Johnson at JC Penney goes to illustrate what happens when a leader gets too far in front of the troops while violating the army’s accepted doctrine. In the case of JCP, the doctrine was the shrine of the customer and the mystical marketing method of using discount coupons to lure a specific segment of discount- happy customers into the stores. Ron Johnson dreamt of a completely new JCP – something where young, trendy millennials would come in and shop, happy to pay more and buy more. Going against almost 100 years of established doctrine, Johnson started a massive makeover of the chain, first by eliminating the big discount coupons that brought discount-hunting shoppers into the stores.

Funny, it did not work out well. Stopping the coupons stopped the flow of a major source of customers. Middle class moms of all colors, in all parts of the country, now did not have a reason to make the trip into a Penney’s store. WalMart does EDLP. But WalMart is not a department store, it is a discount store. Johnson discovered there were not enough other customers that did not use coupons to help weather a sales downturn. The ads that carried the coupons gave the discount-hunters the reason to come into JCP, maybe pick up on the coupon special, and likely buy something else at regular price because it was a fair deal. That model worked for Penney’s since John Cash Penney actually ran the company. Watching JCP struggle, attempting a massive change of customer base, became the approaching train wreck that we can’t watch, but can’t stop looking at as it unfolds.

So doctrine was stronger than strategy; it could crush any strategy that was not in alignment. Good.

I was still restless. Something was still missing.

A soon-to-be new client called me with a tale of woe. Business was growing; a quality problem to have. It was growing so fast that they had real quality problems. They had capacity problems, too. The new sales plan worked and the company signed up almost 20% new customers over four months. But now they could not process all of the business, and because of the volume, were making lots of mistakes. When the order is late and has errors, and the one item you needed for the dinner service tonight is missing from the order, chefs get pissed. When chefs get pissed, they switch wholesalers.

The company had a great business plan. They had the market to themselves on many of the products, but that could change if they could not get their operations in order. Mike and I got busy working with the management team, key workers in the warehouse and the driver team, developing process charts of how everyone thought the processes worked. There were at least three versions of each of the processes. It was clear that sales was not on the same page as customer service, and the warehouse was doing too much rework to get things right. The drivers were great, even as we listened to their stories of having to park before the first stop to rearrange the load to match the delivery schedule.

Together we focused on the operations. They knew their strategy, the commitments they made to customers. They knew their tactics, what to do to get the job done. What they couldn’t do well was execute. The core team was used to a certain level of business, and covering the peaks with overtime. The peaks became the new normal, and everyone worked overtime. It became overtime every day. Everyone liked the extra money. As the volume continued to grow, people were working 12-hour days. It didn’t take long for productivity to drop, for mistakes to increase, and for customers to get pissed.

Clearly, operations, the actual activity of executing the work, is just as important as the other three components. While some people could argue that I am talking about execution of the work, my view is wider and deeper. Because of the variability of supply and demand, from inventory to customers to employees to capital, operations is much more than execution. Operations encompasses planning the work, measuring the performance, and making changes in the operations that make it better. Operations is the realm of Kaizan – 改善. Make better, continuous improvement, the heart of Japanese manufacturing magic.

DSTO is born

The more I thought about these components of leadership, and the more I thought about my experience of where strategy came from, I arrived at the conclusion that the generals don’t own the strategy. Sure, they may decide on the strategy, but the doctrine of the army binds the strategy the generals can commit. Doctrine is policy, the rules of engagement, the political will of the king, emperor, or government that deploys the army. Strategy becomes the commitments the generals can make, the promises they make following the doctrine. The strategy defines the tactics the army can deploy. What is the enemy? How many men, with what weapons, over what time do we need to deliver the objective, the strategy? Then we go into operations to execute the tactics that support the strategy that delivers the commitment to the doctrine.

Doctrine -> Strategy -> Tactics -> Operations -> Doctrine -> Strategy -> Tactics -> Operations -> (again)

DSTO

This may be a radical way of looking at the relationship. Some people don’t agree, thinking that the model is too complicated. Others don’t get it, because it is a complex subject. With four moving parts, the DSTO ring is in constant, self-correcting adjustment. Attempt to go against doctrine too much, or change the doctrine too fast, and the other elements will pressure against the change. A weakness in any one element affects the whole. After a while, the concept just made sense.

Read on in the articles here and decide for yourself if these four elements belong together. It does not matter the organization, from a church to a business; all four elements exist.

Articles in This Series

Articles in This Series

How Doctrine Works

Cats can’t read. Dogs do not understand human language. We can train animals to behave in different ways, triggered by pattern responses, but not with consistency. Pavlov trained dogs to salivate at the sound of the bell, because he conditioned the dogs to expect food when they heard the bell. Read More

Doctrine: Belief Guiding Action

Doctrine has a bad reputation. As with most bad reputations, the degree of badness is not due to the actions of the subject, but the thoughts, opinions, and interpretations of those who choose to judge. Read More

Examples of Doctrine

Doctrine surrounds us, yet many people overlook, misunderstand, and malign it. Some ignore doctrine. Others are ignorant of the impact of doctrine. Read More

Feedback Loops

Years ago, in my college days, I owned a VW Rabbit. The car was one of many that emerged from the first US Foreign Trade Zone in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. That four-door Rabbit was one of many mistakes that rolled out the doors in Westmoreland. Read More

Doctrine of Control

The trade press presents a steady stream of articles about how leading companiesmanage their supply chains. At times, I get the impression that the editors and writers think that whatever new trend a company is “blazing” is a new concept. Read More