Welcome to WATP

An Educated Manager is Our Best Client

At We Are The Practitioners, education is our first goal.

Supply chain management is not simple. Never has been simple. The complex nature of supply networks existed in the days of the Silk Road trade routes to the West Indies, which crossed oceans and linked ancient civilizations. Columbus traveled to find new trade routes to simplify the supply chain of his era, and stumbled into becoming an explorer.

Supply chains are complex networks. They depend on transactions between different businesses, transactions that involve almost invisible intermediaries. A buyer and seller may think they are the only entities involved in a trade transaction, but countless carriers, brokers, warehouses, governments, banks, and agents have a hand in each arrangement. When everything goes right, the buyer and the seller never notice. Let just one of the invisible intermediaries fail to execute, and you could find the buyer at the neck of the seller.

An educated supply chain manager understands the complexity of these networks. However, when faced with changes in suppliers, carriers, laws, processes, or rules, even educated supply managers need help. They need help understanding the changes, help understanding new complexities, and help understanding how to mitigate the increased risk of failure.

That is why this website exists. With over 30 years of broad Supply Chain Management experience, website creator David Schneider wanted to share with other practitioners what he has learned. He started by writing articles for other publications. It wasn’t long before he built a collection of articles that touched on the boundaries of what he knew, what he learned. The collection formed the first version of this site in 2011 and then grew as other like-minded practitioners put their wisdom to the keyboard and contributed to the site.

It wasn’t long before the body of knowledge grew to over 600 articles, published in no specific order than when they appeared. This body of knowledge grew as diverse as the areas of supply chain management. After a few years and a few hundred more articles, it was clear to Schneider he needed to create some form of organization. That effort started with this version of the WATP (We Are The Practitioners) site.

Our information is organized into sections:

Topics – The Art of Analysis, Leadership, Warehouse Operations, Transportation Operations, and Project Management are examples of Topic titles.

Subtopics – contained in each Topic section, they focus on specific areas such as Petroleum Logistics or Systems Thinking.

Article Series – each Subtopic section contains a series of articles such as “Are You Taking Notes?” or “Define Your Victory.” The Article Series are deep dives into the subject matter, exploring many different aspects. Beyond these Series, there are groups of stand-alone articles that focus on a singular subject.

These are not textbook articles. The authors are supply chain practitioners with long careers running large and complex networks, some with over 30 years of practical experience. We don’t pull punches; we are plain spoken and blunt. Some article series are written in story format, like the way Eli Goldratt presented the Theory of Constraints in the business novel, The Goal. We sometimes crack jokes. We sometimes drop colorful language. We even sometimes take on the persona of a 1950’s detective to tell the story, to make the point. While we seek to educate, we also seek to make the process entertaining. Textbook and stuffy does not fit here. Informal, entertaining and informative fits.

These are not textbook articles. The authors are supply chain practitioners with long careers running large and complex networks, some with over 30 years of practical experience. We don’t pull punches; we are plain spoken and blunt. Some article series are written in story format, like the way Eli Goldratt presented the Theory of Constraints in the business novel, The Goal. We sometimes crack jokes. We sometimes drop colorful language. We even sometimes take on the persona of a 1950’s detective to tell the story, to make the point. While we seek to educate, we also seek to make the process entertaining. Textbook and stuffy does not fit here. Informal, entertaining and informative fits.

In 2018 we are working to reformat our content to make it more accessible, easier to find. We are also creating more content in essay format, and adding video and slide presentations of older material.

What we find somewhat amazing is how much of the content has legs, and how popular some of our old content is. Every month, over 2,000 people find our article on reformulated gasoline blendstocks, “The Gasoline BOBs.” We get messages from readers that are not supply chain practitioners thanking us for our articles. We know that through organic Google searches, people find and read over 50% of our material, a clear message that we have created value.

What started out as a simple blog is now a solid resource. We hope that you use our site to find the knowledge and education you are looking for regarding Supply Chain Management.

After all, as we said at the start, “An Educated Manager is Our Best Client.”

Supply Chain Is Hard

If you run a fried chicken restaurant, not having chicken to serve is crippling.

That is exactly what happened to over 800 Kentucky Fried Chicken stores in the UK in February 2018. The supply of fresh chicken stopped.

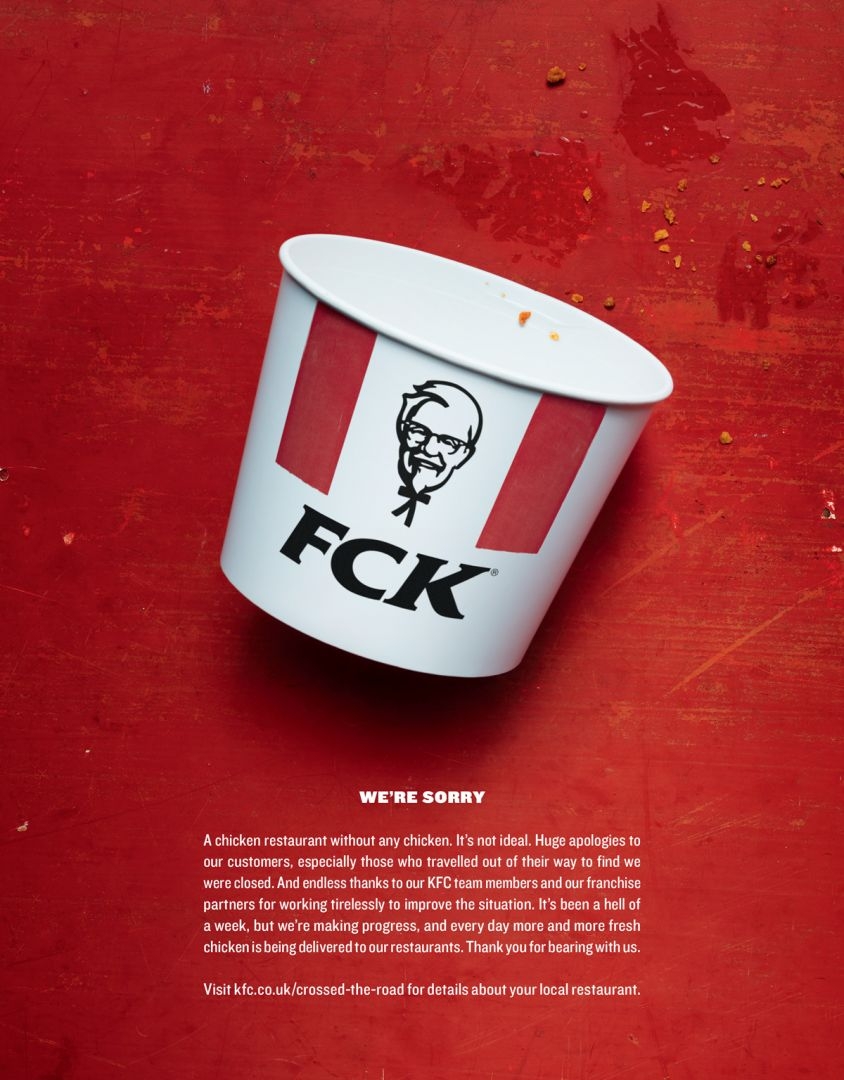

It could have become a PR nightmare for Kentucky Fried Chicken and its parent organization, Yum Brands. But fear not, the marketers at KFC recovered their reputation very quickly by rightfully placing the blame for the failures squarely on the shoulders of their new supply chain partner, DHL. KFC marketers swiftly placed apologetic full-page ads in British national newspapers and swiftly created a website that informed hungry customers when their local chicken shop would be back in stock and open for business.

While late-night comedians cracked wise about chicken restaurants without chicken and KFC’s self-deprecating advertisement that changed the iconic KFC logo to FCK, another company was desperately trying to get a supply chain back in order. The combination of small failures in a critical startup created a huge problem for DHL and its partner, Quick Serve Logistics (QSL).

While late-night comedians cracked wise about chicken restaurants without chicken and KFC’s self-deprecating advertisement that changed the iconic KFC logo to FCK, another company was desperately trying to get a supply chain back in order. The combination of small failures in a critical startup created a huge problem for DHL and its partner, Quick Serve Logistics (QSL).

In November 2017, DHL and its partner won the business of distributing fresh chicken and all of the other supplies to KFC from food distribution specialist Bidvest. Changing a third-party logistics provider is never an easy transition. While we don’t know if KFC planned on saving any money with the change of service providers, we do know that the company was looking to gain market credibility through DHL’s innovation, mainly focused on reducing the carbon footprint of the KFC delivery network.

One week after KFC had to close 90% of the stores in the UK, a spokesman for KFC said that the company was still evaluating the root cause of the disruption. Nobody really knew the single cause of the fundamental breakdown in a brand-new distribution system. This fundamental breakdown created millions in lost sales, both for KFC and the franchise operators of over 700 KFC stores. The employees in the stores suffered from lost pay, since with no chicken to cook and sell, there was no work for them.

When something like this happens, people are quick to find who is to blame. Finding and fixing fault is a natural human reaction. While DHL was loath to have to say anything, they couldn’t hide behind KFC. DHL’s managing director of retail supply chain UK and Ireland, John Boulter, apologized for the “inconvenience and disappointment” of the chicken delivery failure. DHL refused to accept full blame for the problems. “The reasons for this unforeseen interruption of this complex service are being worked on with a goal to return to normal service levels as soon as possible. With the help of our partner QSL, we are committed to step-by-step improvements to allow KFC to reopen its stores over the coming days. Whilst we are not the only party responsible for the supply chain to KFC, we do apologize for the inconvenience and disappointment cost to KFC and their customers by this incident.”

You really can’t blame DHL for wanting to keep a stiff upper lip and their mouth closed. Less than a week after the chicken fiasco came the shortage of gravy for the mashed potatoes. While the chicken was making it to the restaurants in the chain, somehow the gravy disappeared. Within a few weeks the news cycle moved on to something else, and DHL and partner QSL got the KFC supply chain back into alignment.

We may never know the exact root cause behind the failure. There is plenty of conjecture, along with blame, as to what the final straw was that broke the chicken’s back. DHL and QSL are definitely not going to illustrate what went wrong. The only way that any form of root cause analysis will make it to the public eye would be if there is a lawsuit between KFC and its logistics providers. I seriously doubt that KFC would sue, as it must have had a hand in some of the conditions that led to the great chicken failure.

Just because we don’t know the truth does not mean that we can’t make some educated guesses. So let’s start guessing.

Startups always fail

If you have read any of the articles from our series about startup distribution centers, Are You Taking Notes? you will know that I have a rather fatalistic view about the success of any startup operation. Frankly, they all fail in one way or another. Less than half of all startup operations launch without a catastrophe and less than 5% start without issues. That’s why I am so comfortable saying that startups always fail.

The failures do not have to be as fundamentally horrible as what happened with KFC. The failures often manifest as simple teething pain issues, like lost orders, excessive damage, personal injury, inventory inaccuracy, excessive turnover, schedule delays or blown budgets. These are the most common failures that happen with any startup logistics operation. These are the common risks that can happen to not only new operations, but to existing operations.

None of these common failures deal killing blows to an operation. It’s not just one, but a combination of any of these failures that can bring a new distribution operation to its knees. What good managers do in startup operations is accept that some of these failures will happen, but be prepared through good planning to mitigate the effect and keep a chain reaction from happening.

Too many chickens in a single house

Many of the stories about the great KFC chicken shortage focused on the network design. The old service provider, Bidvest, serviced KFC through a network of five distribution facilities. It is reported that each one of these distribution facilities was solely dedicated to the KFC business. There were two suppliers of the raw chicken, shipping from multiple locations throughout the UK and Ireland to the five Bidvest facilities. That all changed when DHL took over and combined all of the distribution facilities into a single point outside of the Borough of Rugby.

Rugby is a market town located in the central UK, about 15 miles east of Birmingham and about 50 miles northwest of London. I suspect that if you did a map plot of all the KFC locations in the UK, the Borough of Rugby would be close to the center of all of the KFC stores, considering distance and store density. I am sure that DHL conducted an extensive distribution network analysis to determine where the best location would be to place a single distribution facility. I suspect that as DHL ran this network analysis, they looked at the options of two, three, four and perhaps five different distribution facilities. I believe because of cost and the desire to reduce the carbon footprint, DHL selected a single facility that avoided duplication of management and duplication of inventory.

Many of the press reports focused on DHL’s selection of a single location, laying claim that this decision was the root cause of the failure. I don’t agree. In the long run, a well-run single facility will outperform a network of multiple facilities by reducing both cost and inventory duplication. The distances in the UK are far shorter than they are in the United States. It is not inconceivable to think that a single facility, properly designed and properly managed, could provide a level of service equal to a multi-location network.

However, when making a switchover from a multi-location network to a single location, the transition should be measured. Just throwing the switch and going from five locations to one is a risky proposition. If I’d been the program manager I would have coached KFC to run a gradual transition, shifting volume from each of the older facilities into the new facility with a four or five-week timetable. That way, if something catastrophic happened, we could shift volume back to the older facilities. While you may think that this is not possible when changing 3-PLs, it is actually quite common and is often negotiated as part of the separation.

Traffic is a bitch

Distribution facilities are often located next to major highways and motorways. Such was the case of the DHL location in Rugby, and news reports claimed that a traffic accident on the motorway near the distribution center prevented trucks from returning or delivering to the DHL facility. The accident reportedly happened on the M6 Motorway, which runs east-west between Birmingham and the M1 Motorway, the major motorway to London.

The DHL facility sits between three major motorways, the M1 to the East, the M6 to the North, and the M45 to the south. If there was a major accident on the M6, depending on where it was, DHL delivery trucks and the inbound trucks bringing chicken to the facility could’ve been stopped in the traffic jams. However, I find the reported story of the traffic jam being the root cause as dubious. Truck drivers typically are not stupid, and once they discover that a major highway is closed, they tend to look for alternate routes. Unless the drivers were all new and did not understand the road network around the DHL facility, I doubt that traffic played a significant role in the failure. It might have been a contributing cause, perhaps the straw that broke the camel’s back, but not the central cause.

New is abnormal

New facilities mean new systems, new equipment, new managers, new processes and new people. Mixing all of this new into a single space creates an abnormal environment. Again, from our Are You Taking Notes? series, startups are “abnormal fighting to become normal.” The same problems that you might have run into in an older facility manifest into something completely different in a new facility. New operations discover surprises with the simplest of systems and issues. Undoubtedly the new DHL facility had its share of abnormal events.

Complexity invites disaster

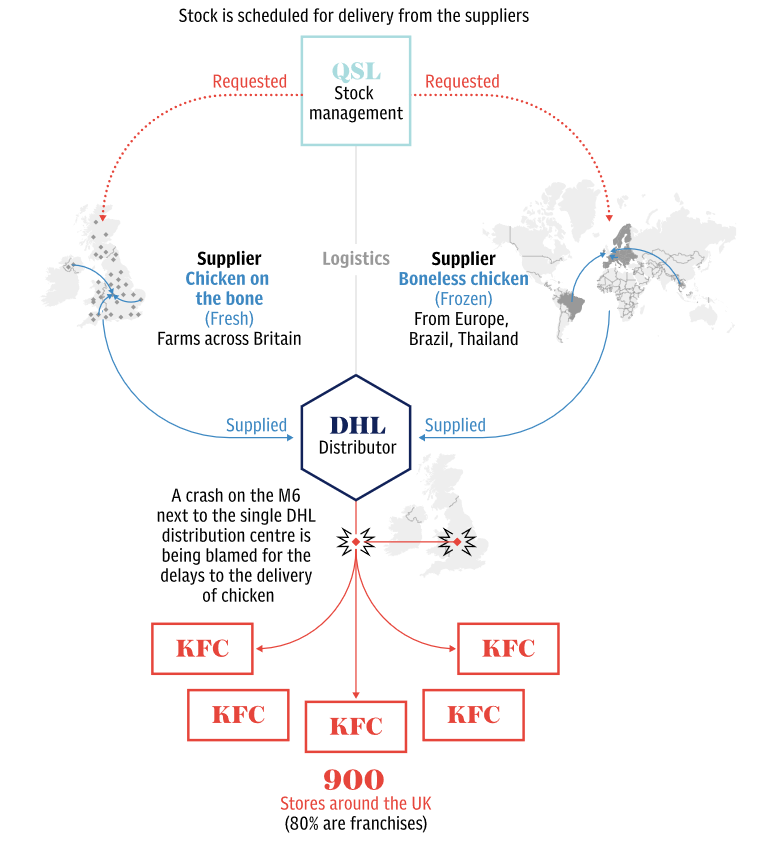

The UK newspaper, The Telegraph, published the graphic we show to the right. In a stylized form, the graphic illustrates the information, decision and physical flows in the KFC network. QSL, using sophisticated inventory management software, pulls sales data from the stores, issues orders to suppliers and processes the order management for the resupply of the stores.

The UK newspaper, The Telegraph, published the graphic we show to the right. In a stylized form, the graphic illustrates the information, decision and physical flows in the KFC network. QSL, using sophisticated inventory management software, pulls sales data from the stores, issues orders to suppliers and processes the order management for the resupply of the stores.

The chicken suppliers ship from the farms and processing plants to the DHL distribution facility. The chicken suppliers control the freight movement, hiring the truckers who pick up the fresh meat from the processing centers and deliver it to the DHL distribution facility.

DHL provides the physical distribution of the chicken and other components to the 900 KFC stores around the UK.

Three different entities, each separate businesses, partnered together to serve a single customer. As this was a newly started operation, it is not surprising to think that there would be problems in communication and control of the movement of chicken meat from the suppliers through the new network. This is a complex network that is moving a fresh and perishable food that requires controlled temperatures and specialized hygienic handling methods. I suspect that the truck drivers carrying the deliveries from the processing plants to the DHL facility weren’t as familiar with the driving times or the traffic patterns to get to the new distribution location. Likewise, the DHL delivery drivers faced the same challenges of new patterns and delivery parameters.

A combination that flattened the chicken

As I said in the beginning, no single event created the KFC chicken shortage. It was a combination of different events and the misfortune of timing that magnified DHL’s operational failures. I am sure that the DHL management looked hard for the causes, and that there were many private (but I wager not quiet) conversations between KFC and DHL about recompense for the lost sales at the stores and the lost wages of the store employees. I am also sure that there was some blame sharing, as the client is never innocent with a transition like this. That it took over two weeks to get the chicken supply back on track, followed quickly by the gravy shortage, indicates there is something wrong in the relationships between KFC and their suppliers.

For now, the chicken is crossing the road, hoping to not be flattened on the way to the fryer.

Dave's Bookshelf

We didn't learn everything we know on the fly.

Here are some of the most useful, innovative,

and timeless books we've ever read.