"We supply chain managers maintain and feed a conceit that we understand and employ systems thinking in the execution of our duties."

That is how my article in Supply Chain Digest started. Actually, it was two articles, a Part 1 and a Part 2. You can read them below, too. I was not kidding about my opinion about managers and systems thinking.

Systems thinking is an approach to problem solving that looks at problems as part of a system. When working with an organizational structure, like a supply chain, the system is the combination of the people, structures, processes, and environment that work together (or don’t work together) to create a desired outcome. A healthy system delivers the desired outcome. An unhealthy system delivers unintended consequences.

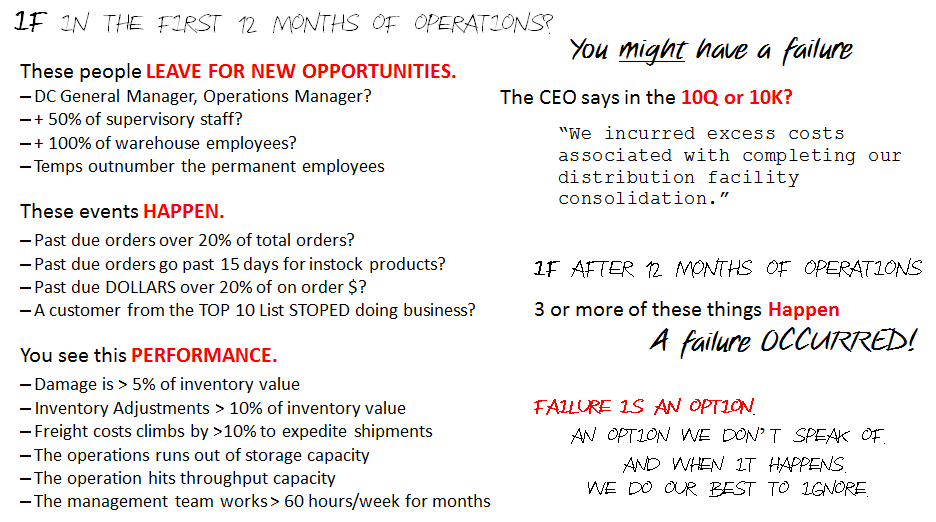

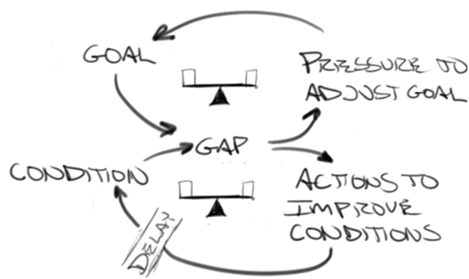

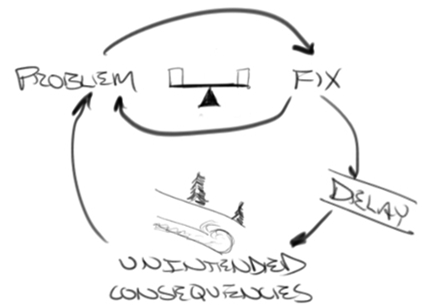

When things go wrong in a system, the result (what went wrong) is often the symptom, not the cause. People pay attention to the symptom, not the cause. If it is safety related we may move quickly on it. When process change is needed, we hear much about pealing back the layers and getting to the root cause of a problem. However, the conceit held by most managers is that the problems are easy to fix, that training people better (just training them to start with) or adding more technology will fix the root cause. We can ask “Why?” five times, or do fishbone charts. Great lineal thinking! That logic comes from the Toyota Production System (TPS) and the famous 5 Whys of Six Sigma thinking. Yes, they help solve problems, but only localized problems. The methods work when the problem can be localized. But they don’t work for large, complex problems, like climate change.

The key to TPS and 5 Whys is the concept of acceptance: you fix what you can fix in your own sphere of control and influence. If the cause of a problem is outside of your sphere of control, the assumption is that the condition can’t change, so your processes must conform to the constraints created by the entities outside the direct process.

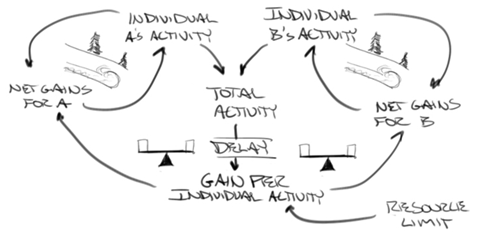

I never liked accepting that you can’t fix a remote cause of a problem in a system. Acceptance is not necessary or even right. We can change and influence the behavior of people in other departments in our own companies and people working in other companies. We can change the behavior of companies. That can come contractually or by the influence of practice.

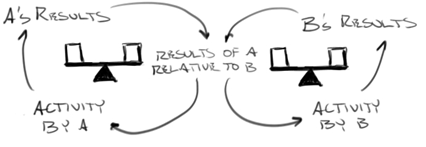

To do it right, you have to know about systems thinking, and be able to look at the broad view of the problem as part of the system. The problem happens because some event elsewhere fails to stop a undesirable outcome, or worse, the event that makes the decision does not happen. Decisions made or not made, across the globe or across the hall, affect the outcome of other events.

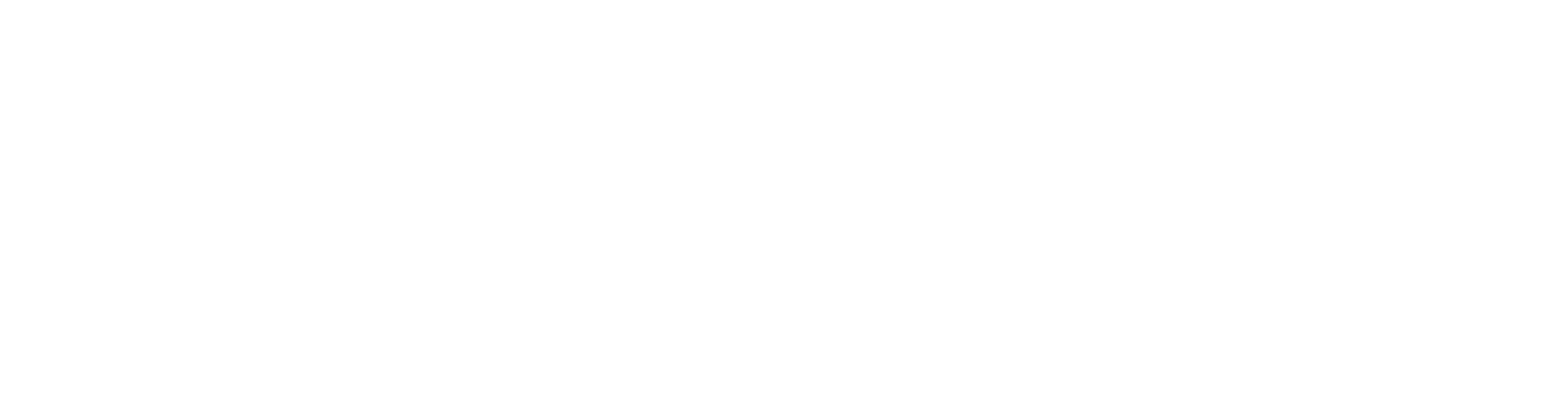

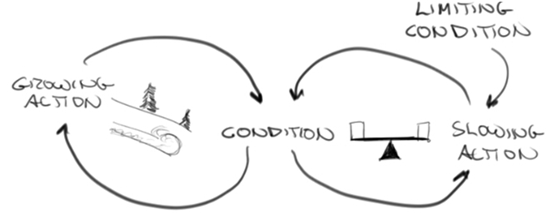

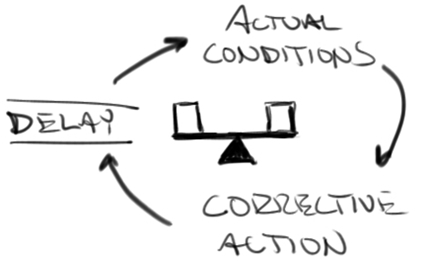

That is where systems thinking methods come into play. The challenge is more than fixing problems in a current system; it is developing new systems that replace the current ones that are allowing failure to happen. Systems thinking take a holistic view of the entire system, the constraints, the influences, the motivators, in all of the enterprises and entities involved in the system. Sometimes these systems are complex, sometimes very simple. The one thing in common is that they operate in loops.

Loops are how many things work in life. When we define a process as a straight line, we are really just taking a short section of a larger system. In flowcharting there is always the “loop” function.

In this topic, we introduce the concept of systems thinking. There are a number of more technical articles about what it is and how to use it. There are also narrative descriptions of how to apply systems thinking in a Warehouse. If you want to know more, just start digging into it below.