So, How Does an

Oil Company Lose Money?

In early 2012, a New York State based client asked us if we thought that diesel prices would reach $5 per gallon. We looked at the situation and determined that the price should stay under $4.50 per gallon of diesel in the Northeast US unless something happened that altered the balance of refining capacity in the Delaware Valley.

In our analysis, we saw several different scenarios that could drive the cost of diesel above $5 per gallon. Almost all would pertain to the loss of any refining capacity at the remaining Sunoco refineries or changes in how diesel refined in Gulf Coast refineries moved to the Northeast.

The following is the second report that we shared with the client that focused on the background behind the concentration of refining capacity on the Delaware River and then tenuous situation of the Sunoco refineries.

So, How Does an Oil Company Lose Money?

In our last report I posed the question, “Can an oil company lose money?” I gave the short answer as “Yes,” and presented the Sun Oil Company as the exhibit.

As I shared in that report, there are many moving parts in this story. It is a complex story, and we should look at each of the parts, and the potential failures of each of these parts, to understand how they affect the price of diesel in the Northeast. For this all to make sense, we must dig in and look at each part. Some parts have to do with activity across the globe, and some with activity just around the corner. But first, we look at a little bit of history that led us to today.

You might wonder why we are going into the history, but please bear with us; the history helps define the forward problems in the market today.

A Little History About Sunoco (and Delaware Valley Refining)

Sunoco is an old company, having started in 1886 with the purchase of two oil leases near Lima, Ohio. In 1890 it became the Sun Oil Company of Ohio and acquired its first refinery in 1894. In 1901, the company purchased 82 acres along the Delaware River in Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, that became the second refinery, where the company processed crude oil shipped by tankers from Texas. With the Marcus Hook refinery, Sun Oil built its East Coast future on crude delivered by tanker.

Sun Oil vertically integrated, creating control over its supply chain by building and sailing its own tankers to carry oil from the Texas fields to the refinery on the banks of the Delaware. The company diversified into the shipbuilding business in 1916 when it established the Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. Sun continued its vertical integration by opening its first service station in 1920 in the Philadelphia suburb of Ardmore.

Through the 1930s, oil refining depended on distillation processes until Sun placed the world's first large-scale catalytic cracking plant in the operation at Marcus Hook in 1937, greatly increasing the product yield from the crude. Sun continued to innovate refining processes at Marcus Hook to increase product yields.

Throughout this initial growth, Sun continued to pull crude oil from far and near via tankers. Sun tankers hauled crude from faraway places, like the massive Lake Maracaibo oilfield in Venezuela. Sun was the first player in the Canadian oil sands with the Athabasca sands project in 1967. The refinery worked with the light oil from Texas and the heavy from Venezuela and Canada, and the company continued to invest in capacity.

In 1968, Sun merged with the Sunray DX Oil Company, picking up oil fields, refineries and gas stations in the mid-west of Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, all the way to Texas. Expansion continued in the 1980s with the purchase of the Texas Pacific Oil Company, spreading under the DX name. Sun also took a position in coal when it acquired reserves from Oak River resources. Throughout the early 1980s, the company kept buying resources, buying into offshore production in the North Sea and off China, and adding more domestic resources. The company continued to explore to feed the refineries.

As Sun Oil grew, so did other major oil companies, like Atlantic Petroleum, Gulf Oil, Richfield Oil, and Standard Oil. Over the past century many refineries opened, merged, grew or closed. All depended on delivery of crude by tanker, and in some cases the shipping of refined products.

The 1980s was difficult on the vertical-structure oil companies. At Sunoco, all resource growth halted in 1988 when the company restructured, selling off all of the domestic oil and gas exploration businesses to focus on the downstream part of the business, from refining to marketing. The company sold off the international exploration business in 1996, becoming a complete downstream player.

Using the money from the sale of the exploration and production businesses, Sunoco acquired other downstream companies, picking up the Atlantic Petroleum Corporation in 1988, adding a refinery based in Philadelphia (the oldest operating refinery today) and a network of gas stations and pipelines. In 1994, Sunoco acquired Chevron's Philadelphia refinery that was adjacent to the new facility, combining the two into a single refining complex. Via pipelines, they could link directly with the Marcus Hook refinery.

Throughout the rest of the 1990s, Sunoco continued to divest of a wide variety of businesses it picked up in its first century, selling a real estate business, the Canadian tar sands, and the mining businesses. By the end of the 20th century, Sunoco became a large independent US refiner/marketer in the Northeast. The company continued to grow its retail front, acquiring Coastal and Speedway service stations from ConocoPhillips.

Over all of the years of growth, the original Sun Oil, and the other acquired companies, built transport assets, like pipelines, terminals and loading facilities. Over time, the company merged the transport operations, an entity that could stand alone. In 2002 Sunoco spun off the terminal and pipeline business, creating Sunoco Logistics Partners L.P. Sunoco still owns about 34% of Sunoco Logistics. (Remember this, it will come up again in a later report.)

Sunoco was a profitable refiner, distributor and retail seller of petroleum products, including gasoline, diesel, home heating oil and various chemicals.

That is, until the refining business turned sour.

Profits and Cash Flow

From 2000 to 2008 Sunoco increased revenues, doubling from 2004 to 2008. In 2004, Sunoco kicked off the expanded growth by buying the Eagle Point refinery from El Paso Energy. The refinery came with a large network of delivery pipelines and a solid tank farm. After-tax net income wasn't as rosy and net margins dropped from 2.88% down to 1.43% the same time of the doubling of revenue. While shareholder equity improved, Wall Street definitely wasn't happy with the growth and the earnings. When Wall Street isn't happy, leadership changes happen, hence the introduction of a new CEO in late 2008. As the American economy suffered the body blows of the credit crisis, Sunoco ended fiscal year 2009 with the loss of $329 million EBITDA.

As many other companies did in 2010, Sunoco executed a business improvement initiative targeting over $300 million in cost savings. Drastic times called for drastic measures, and Sunoco’s cost savings plan included the shutdown of Eagle Point and the sales of the Tulsa and Toledo refineries to other refiners. The cost saving measures helped Sonoco earn $234 million in net income in 2010. The highlight for the year was refining's $500 million turnaround in pretax earnings, largely a part of improving cost structure and margin capture.

The happy days of 2010 did not extend into 2011. No matter how much the company could cut its costs, the reality of the open market, the chemical structure and locations of its refining network set it up for massive billion-dollar losses.

Crack Spread and Competition

If you listen to the financial reports on CNBC about oil prices, you'll hear the strange terminology of the oil industry. One term that becomes very important in this discussion is crack spread. Crack spread is nothing more than the difference between the price of crude oil and petroleum products extracted from it, so crack spread is really the gross margin a refinery can expect. The most important factor affecting crack spread is the product mix the refinery makes, the proportion of the various petroleum products including gasoline, kerosene, diesel, heating oil, jet fuel and asphalt.

A host of factors will affect the product mix of a specific refinery. Regional demands of different kinds of products will have a direct impact. The mix of the refined products also depends on the particular blend of crude oil feedstock processed by a refinery. The capabilities of the refinery itself limit its ability to change its product mix. In essence, there are three major drivers to the gross margin a refinery can make: the cost of the crude, the demand for the various petroleum products, and the capability of the refinery to convert crude into finished product.

This is where the remaining Sunoco refineries hung an incredible millstone around the company's income statement.

Sweet vs. Sour Oil – It’s on the Menu Again.

After Sunoco shut down the Eagle Point refinery in 2010, only the Philadelphia complex and Marcus Hook refineries remained on line. Both refineries made significant upgrades ($285MM) in environmental and safety systems after strikes and fires in 2009.

Both of these refineries are designed for the sweet crude that comes from the North Sea and the Arabian Sands. Heavy crude oils contain a higher proportion of heavy hydrocarbons, composed of longer carbon chains. Heavy oil is much more difficult to refine into lighter products such as gasoline without using sophisticated processes. The Sunoco refineries didn't have the hydrocrackers and other processes needed to break down the heavy oils.

The company had invested a great deal of capital in upgrades at both Marcus Hook and Philadelphia to upgrade its ability to make gasoline that met EPA standards in the Northeast. Both of these refineries went through the significant capital upgrades in the early and mid-2000s. At that time, gasoline demand was growing at a rapid pace, and Sunoco bet heavy on that continuing trend. The refinery upgrades would take multiple years to return the investment, but at the time of the decision, the bet look good. Americans were embracing larger vehicles that burned more gas, driving more miles, and crude oil was a relatively inexpensive $60 - $70 per barrel.

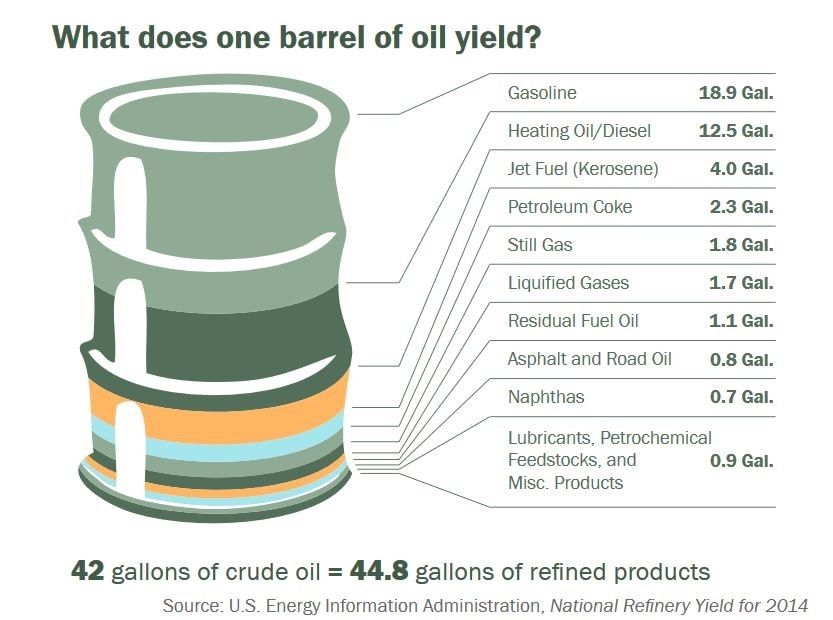

As the chart above illustrates, there are 42 US gallons in a barrel of oil. It never converts into all gasoline, or diesel. In fact, depending on the crude oil chemistry and the refining process, the yields can change a great deal. In July 2011 crude cost Sunoco $3.45 per gallon at market prices. Reformulated Regular Gasoline sold between $3.50 and $4.00 in 2011 – so the crude to gasoline crack spread was about forty cents (40¢). Even with hedging and forward contracts, Sunoco was in a margin squeeze, as was every other oil company that had to buy crude in the market. If Sunoco could get excellent pricing for the other products that come out of the 42 gallons of crude, they might make up some gasoline losses. However, in the economic conditions of 2011, Sunoco did not have enough strength to buck the market prices on many of the other products.

As the chart above illustrates, there are 42 US gallons in a barrel of oil. It never converts into all gasoline, or diesel. In fact, depending on the crude oil chemistry and the refining process, the yields can change a great deal. In July 2011 crude cost Sunoco $3.45 per gallon at market prices. Reformulated Regular Gasoline sold between $3.50 and $4.00 in 2011 – so the crude to gasoline crack spread was about forty cents (40¢). Even with hedging and forward contracts, Sunoco was in a margin squeeze, as was every other oil company that had to buy crude in the market. If Sunoco could get excellent pricing for the other products that come out of the 42 gallons of crude, they might make up some gasoline losses. However, in the economic conditions of 2011, Sunoco did not have enough strength to buck the market prices on many of the other products.

Integrated players like Exxon, Shell, BP and ConocoPhilips made a good margin because they produced (pumped) crude. Sunoco had strategically bowed out of the exploration and production side of the industry 20 years before, so they had to buy oil from other producers.

The oil Sunoco had to buy for the Philadelphia refineries was light sweet crude. By design, the engineers and managers at Atlantic Richfield and Chevron refineries decided the feedstock for the old refineries that Sunoco bought. The twin refineries in Philadelphia processed light sweet crude, delivered by tankers, into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and many other hydrocarbons. A design decades old, this refinery needed oil delivered by tanker.

Another Part of the Puzzle - Logistics

So how does Sonoco get the oil to feed the Philadelphia refinery complex?

Remember the history of the company. Sun Oil built Marcus Hook on the banks of the Delaware River, feeding a crude oil from the tankers that the Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company built in Chester, Pennsylvania. That is how the refineries in Philadelphia and Marcus Hook got their crude.

Transportation is part of any supply chain story. Just as sourcing, pricing, manufacturing and storage are part of the supply chain story. The availability of alternate feedstock into any process is the concern of the supply chain manager. The more locked-in the supply chain is to a specific source or specific transport method, the more vulnerable the enterprise becomes.

Where does light sweet crude come from? The North Sea, Nigeria, West Texas, and North Dakota. The light reference comes from the specific gravity of the oil, about .830. The sweet from the sulfur content, which for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) is 0.24% and for Brent crude is 0.37%.

Light sweet crudes are the barometers used in oil prices. WTI trades on the New York Mercantile Exchange. Brent (aka LCO) trades on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE).

Refineries in the mid-west and the gulf get access to WTI via the massive terminals at Cushing, Oklahoma. The oils flow into the terminals in Cushing and flow out on a huge pipeline system. However, the pipelines that carry crude oil don’t reach up to Philadelphia. Even as Sunoco Logistics has an extensive network of pipelines around Cushing, the only mainline crude pipeline it controls leads to Toledo, Ohio.

Sunoco’s refineries, and every other Delaware River refinery, had the same logistical constraint. They could only take inbound tankers.

Our next report focuses on how to ship crude oil – via ships, trains, pipelines and trucks.